Prize Money in the Royal Navy 1793-1815

Posted April 10, 2020 by Ryan Moore

HMS Psyche was built in a trying age fraught with challenges and hardship for the common seaman. The approximately 150,000 men (and some women!) who manned the ships of the Royal Navy by the time of the War of 1812 had little to look forward to except monotonous routine, bitter weather, risk of disease and death (sound familiar?). The pay wasn’t great, often deferred, and regularly reduced once finally issued. Yet there are many recorded instances of common seamen volunteering and serving in the Navy for decades. There were some compelling reasons to enter into and stay in the Navy life.

Regular food in substantial quantity, the chance to move up through the ranks, or an escape from crushing poverty or criminal condemnation ashore were incentives. Camaraderie, adventure, and a chance for glory also played into it. There was also the potential of prize money, which having just read ‘Post Captain’ in the Aubrey-Maturin series, is top of mind for me today.

Prize money encompassed a ‘bonus’ payment for the capture of enemy ships or the destruction of enemy shipping or stores. The value of the prize money was determined by the Prize Court, which adjudicated the legality of the prize (neutral ships were particularly sticky) and the value. The value included the captured ship herself, head money representing the crew compliment (£5 a head), and the value of any stores or goods within her. There were also legal and agency fees to pay, especially if a captain was not able to attend the prize court and/or wished to draw upon the prize money before adjudication, in which case the prize agent would advance a discounted amount of money then collect the bulk from the courts and pocket the difference. Some agents absconded with the money altogether.

The rules and regulations for prize money were enacted by Parliament at the beginning of each conflict, and rarely updated through the course of the 18th century. In 1793, the commanding admiral, captain, wardroom and gunroom officers received 3/4 the value of the prize money, and the common sailors had to settle for the remaining 1/4. An update in 1808 modified the distribution between captains and admirals, reduced the classes for distribution, and gave 1/2 the value of the prize to the junior officers and seamen.

Therefore in 1808 until 1815, prize money was distributed by class as follows:

1/4 - Captain – of which 1/3 would be given to any qualifying admiral

1/8 - Wardroom Officers and Standing Officers (Lieutenants, Captain of Marines, Master, Purser, Surgeon, Chaplain, Gunner, Bos’un, Carpenter)

1/8 - Senior Warrant Officers (Midshipmen, Clerk, Armourer, Ropemaker, Caulker, Sailmaker, Cox’un, Yeomen)

1/2 - Junior Officers (cook, carpenter’s crew, etc.), all seamen, landsmen and boys

….. the portion to be distributed equally between all members of each class.

Pay for officers in 1814 depended on the ship they were assigned to. Psyche, being a 5th rate 54-gun frigate with an expected crew of 280 sailors, would have warranted a post captain and 3 to 4 lieutenants. As there was only one post-captain on the Great Lakes (Commodore Sir James Yeo), all the ships were commanded by a variety of lieutenants (dubbed ‘commanders’ when in command of a vessel). It is unclear who would have commanded Psyche had the war continued on, but let’s assume Yeo would have assigned one of the lieutenants that came with him up the St. Lawrence in 1813. Without a captain, Psyche would not have been rated and would have been deemed a ‘sloop of war’ with a commander.

A commander of a sloop of war would normally be paid 272 pounds, 19 shillings, and 7 pence a year. After income tax, his net salary would be 245 pounds 13 shillings 4 pence. An ordinary seaman would get 13 pounds, 10 shillings per year, assuming it was actually paid out in full, which was not always the case. Our beloved cook would be paid 12 pounds, 4 shillings per year.

Prize money offered an incredible opportunity to supplement these meagre wages. By 1814 there was minimal shipping on the Great Lakes, given all the merchant vessels had been requisitioned into the respective naval fleets, or had been captured or sunk by storms. If Psyche were able to take an American transport vessel, such as the sloop Asp, with a crew of 45, undamaged and laden with military stores, Asp might fit into the ‘average’ value of prizes captured by the Royal Navy at the time. Daniel K. Benjamin’s lovely essay “Golden Harvest: The British Naval Prize System” pegs the average value of a Royal Navy prize as £2300. (This essay is now included in the ‘Documents’ section for your interest.)

So, £2300 would be distributed amongst the Psyche’s crew as follows:

Commander - £575

Wardroom and Standing Officers: £287.10s, to be distributed to each member of this class

Snr Warrant Officers - £287.10s, to be distributed to each member of this class

Jr Officers and Crew - £1150, to be distributed to each member of this class

Let’s say of the 280 officers and crew, there were 30 officers of the first three classes, and the remaining compliment of 250 was made up of sailors, marines, junior officers, boys, etc. That £1150 becomes £4.12s each! It’s not much, but it amounts to about 3 month’s worth of wages for a single day’s work for the average sailor. You tell me if that’s a compelling offer!

Images:

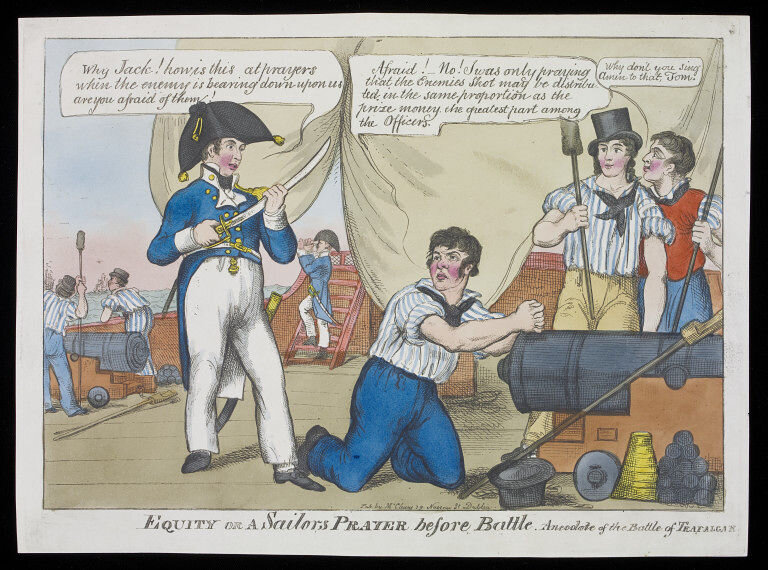

Cartoon: A sailor prays that the distribution of enemy shot follows the same distribution formula for prize money! This cartoon seems to follow the Battle of Trafalgar so likely precedes the 1808 revisions to the prize money formula.

Coinage: This shows what a sailor’s share aboard HMS Psyche would look like, based on the calculation in this post. 4 guineas and 6 shillings. Note: 1 gold guinea is worth £1.1s.

Frigates: The ships of Yeo’s squadron attack Oswego in 1814. In the foreground is HMS Prince Regent, a 54 gun frigate built in Kingston, similar to HMS Psyche.

Sloop: An American sloop, similar to USS Asp.